How Git really works: The mental model you need - Part I

You've probably all been in that place where you think you get it, and then reality leans over and says, “Are you really sure?”. If you’ve been reading my previous blog then you see that I had such a moment when I was assigned to develop a full-fledged security feature based on JWTs. And today? Today, Git showed up and said: “You’ve used me for years… but do you actually know what I’m doing?”.

And to be honest that’s a fair question. Most of us learn Git like we assemble IKEA furniture: follow some steps, ignore others, end up with a few mysterious leftover parts, and trust that whatever you built won’t fall apart immediately. But underneath those familiar commands is a simple, elegant model that explains why Git behaves the way it does, including those moments when it absolutely does not behave the way we want. So before we dive into merges, rebases, or that mysterious thing called HEAD, let’s slow down and look at what Git actually is on the inside.

This blog will be the first part of a two-piece series about the inner workings of Git. So, without further ado, let’s start at the place where everything in Git begins: the commit.

The commit

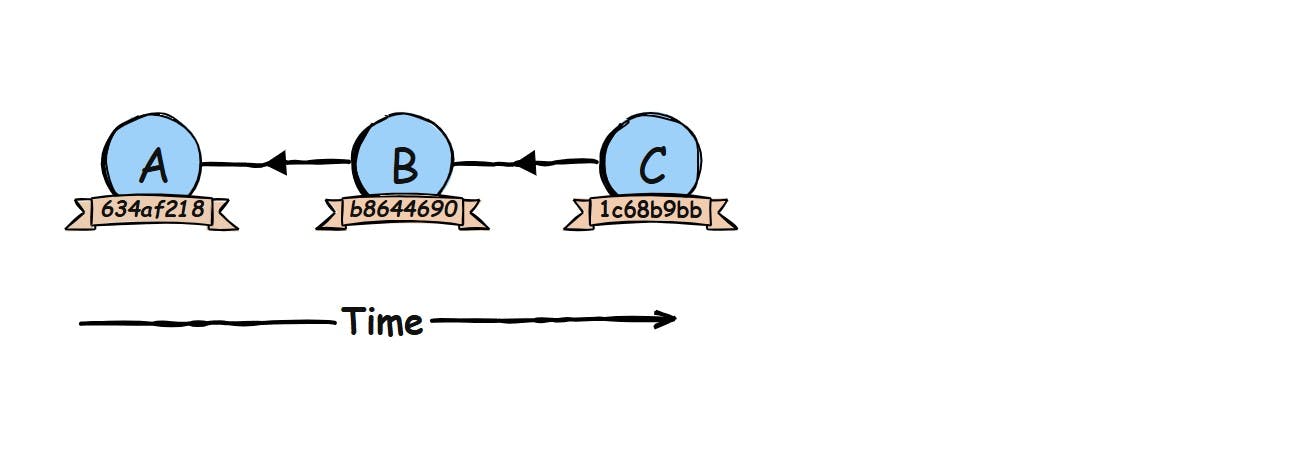

In essence, a commit is a snapshot of your entire project you are working on. All your classes, interfaces, Spring beans, configuration and all of that good stuff is in one single commit. Therefore we can say that a Git repository is basically a database full of snapshots. But wait! If you have all those snapshots of your whole project, doesn’t that take up a lot of space on your hard drive? Yes, it sure would, if Git would store every file in its commits, even if a file didn’t change. Fortunately for us, Git has a smart way of storing your project files in your commits. Let’s take the diagram below as an example.

We start our project, create a Git repository and off we go. We add a pom.xml to our project and maybe also a handy .gitignore file. When we issue that first git commit then that commit contains, as expected, the two files we just created. But with one nuance.

The files are created and stored separately as blobs, “floating” in the repository waiting to be referenced. The commit itself has a tree which stores references to the blobs/files. Not only the files get stored. The commit also stores metadata describing the commit itself, like author, date of committing. The commit itself is identified by a hash (SHA), a 40-character unique ID derived from the commit’s contents. In my diagram I only use 8 characters for clarity and brevity.

Internally Git stores the following in a commit:

- A tree - a directory listing for the commit. It stores filenames, subdirectories, file modes, and references to blob or subtree objects.

- Metadata - parent commit ID, tree ID, author/committer information and message.

Important to note here: Git doesn’t store “Commit ID” inside the commit. The commit is the object and the commit ID is the hash of the object.

What happens when I add another file and commit that to Git? Does Git then store all three files again? No, and that’s the beauty of Git’s storage model. Conceptually, every commit is a snapshot of your entire project. But Git stores these snapshots very efficiently:

- New or modified files: Git always creates new blob objects. The whole content of the file is stored in the blob object. Just to be clear, a modified file is also stored completely in a new blob object, not only the changed part of the file.

- Unchanged files: Git simply reuses the existing blob objects, the new tree points to the same blob IDs used in earlier commits.

Each commit has its own tree object (a directory listing). This tree lists all files in the commit, but most entries point to already-existing blobs and subtree objects. So Git avoids storing redundant data while still giving you full project snapshots at every commit. And this storage model is also a big reason why Git feels so blazingly fast: most operations simply move pointers or reuse existing objects instead of copying entire files around.

Now that we know what a commit actually is, it’s time to see how Git keeps track of them. Let’s have a look at branches.

Branch

When developers start to learn Git, they often imagine a branch as a separate copy of their project. A full folder somewhere with its own set of files. But that’s not how Git works.

A branch does not contain files.

A branch does not contain commits.

A branch does not hold a “copy” of your project’s history.

These assumptions come from other version control systems, but in Git they lead to confusion.

So, what is a branch?

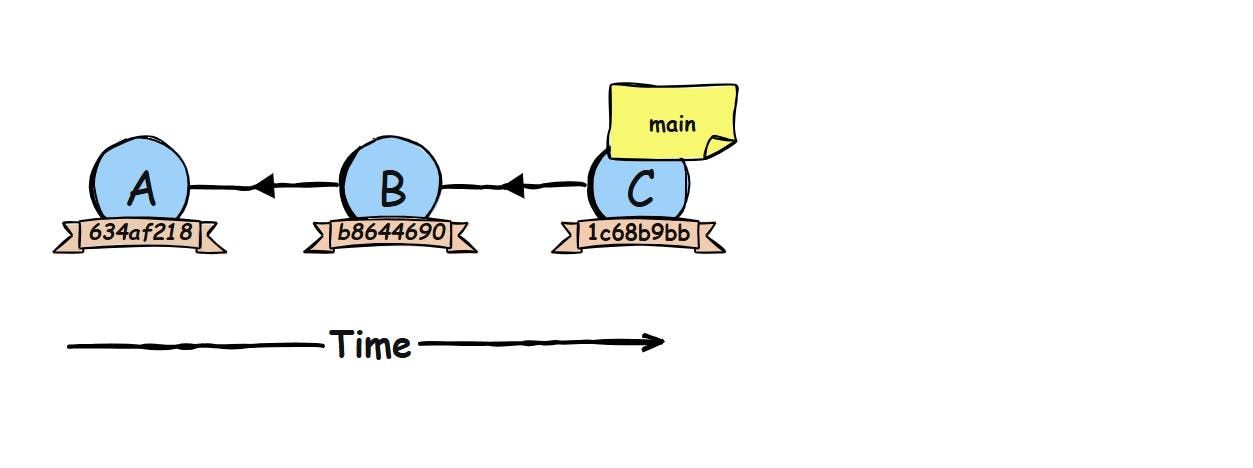

A branch in Git is nothing more than a movable label, a little sticky note, that points to a specific commit in your project’s history.

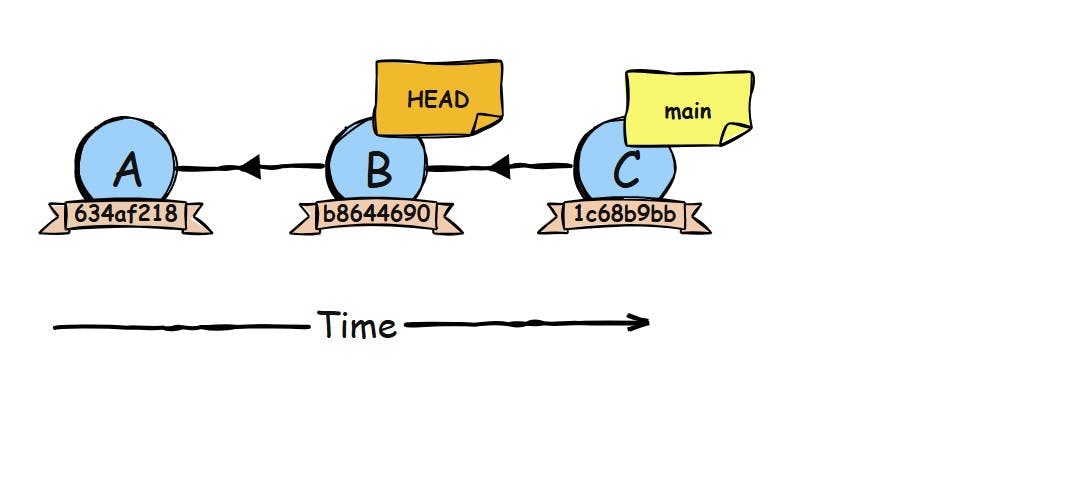

In the beginning, your repository usually has just one branch: main. This branch is simply a pointer attached to the latest commit. Whenever you make a new commit, Git moves this sticky note forward to the new commit. That’s it! A branch doesn’t “contain” commits, it just points to one. Git then follows the arrows backward from that commit to reconstruct your entire history.

So, when we talk about a branch we are actually talking about where the sticky note is attached. Nothing more, nothing less.

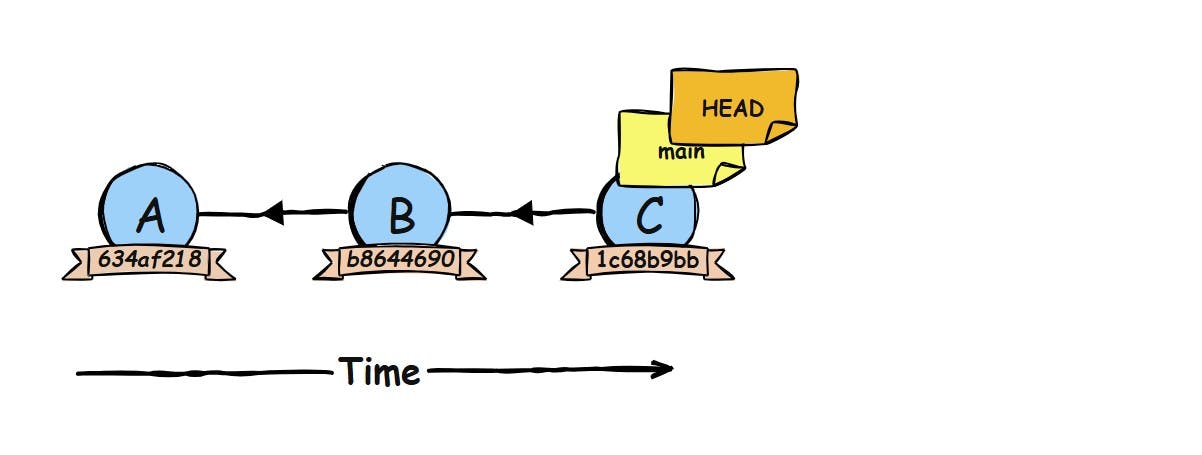

Branches are basically sticky notes attached to commits. But Git has another sticky note, one that isn’t about history, but all about the current commit. That sticky note is HEAD.

HEAD

In Git, HEAD is simply your ‘you are here’ marker. It tells Git which branch you’re currently working on. Most of the time, HEAD doesn’t point to a commit directly. Instead, it points to a branch, and that branch points to a commit. In other words, HEAD is a sticky note attached to another sticky note (the branch), which in turn points to a commit.

When, for example you issue a git checkout main you could see something like this:

This means that: you’re on the main branch. Any new commit you make will move the main branch forward. HEAD just stays attached to that branch name.

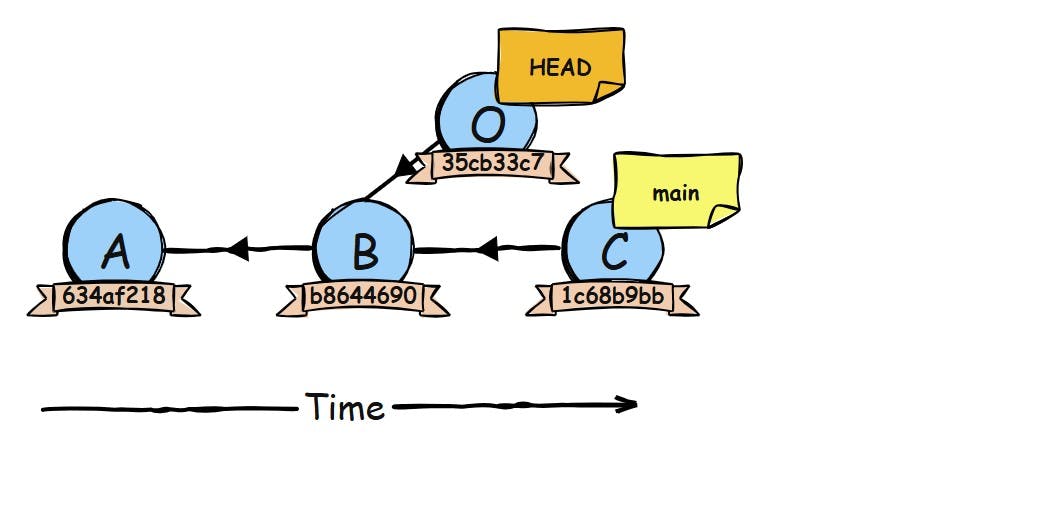

For 99% of the time a HEAD sticky note points at a sticky note of a branch, but if you check out a commit by its hash (git checkout b8644690) instead of a branch name, HEAD now points directly to that commit. This is called a detached HEAD. You can still make commits and all, but they won’t move any branch label.

If you create a new commit in this state, Git will set its parent to the commit you checked out. In the commit graph, the new commit O looks completely normal. It points back to its parent commit b8644690, just like any other commit points to its parent. However, if you look at the main sticky note and follow its chain of parent commits, you will only see commits C, B, and A. Commit O is not part of that history. That’s why we say O is “detached” from any branch: the commit exists, but no branch name refers to it.

Now that we understand what branches really are, simple sticky notes pointing directly at commits, and how HEAD tells Git which branch we’re currently on, we can finally start working with Git in a practical way. So let’s take a look at how you actually check out a new branch and what happens behind the scenes when you do.

Time to develop that feature

One of the first things you’ll do in any real project is create a new branch to start developing a feature or fixing a bug. This is where the power of Git’s simple branching model really shines. Instead of copying files or creating separate directories, Git just creates another sticky note and attaches HEAD to it. Fast, lightweight, and painless.

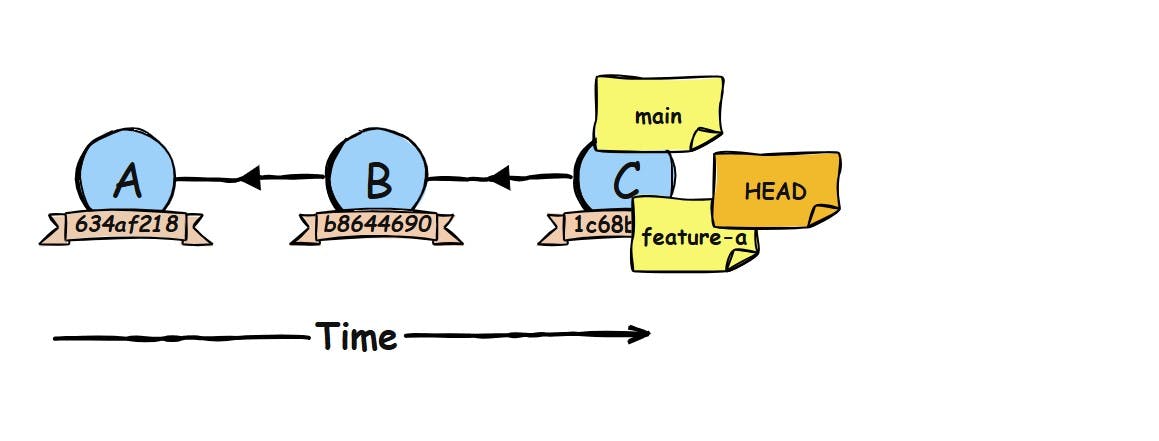

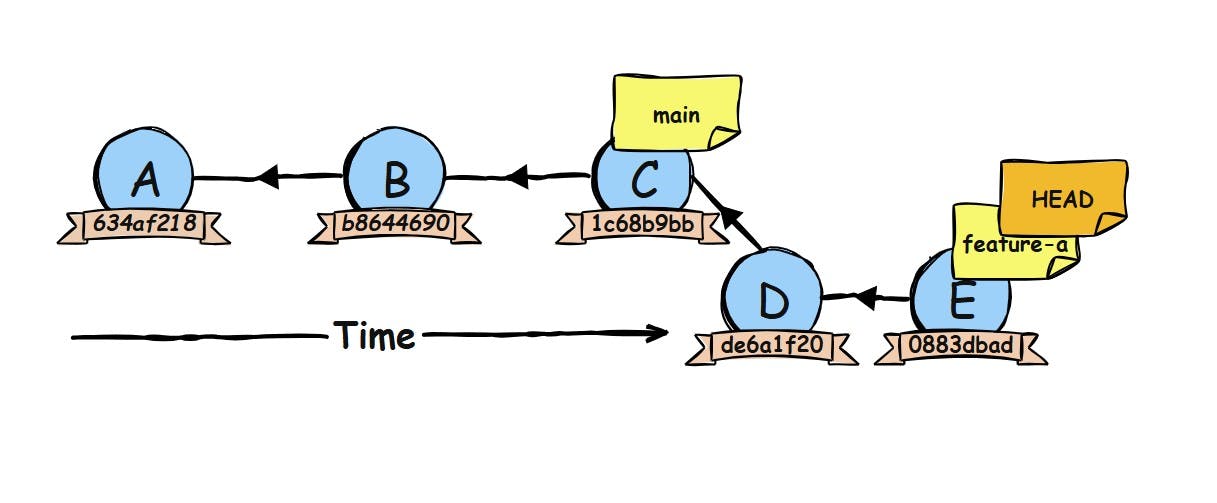

Running git checkout -b feature-a creates a new sticky note named feature-a and immediately attaches HEAD to that sticky note. From that moment on, any new commit will move feature-a forward.

Switching between branches is just as easy: Git simply moves the HEAD sticky note to a different branch label. No file duplication, no heavy operations, just lightweight pointer updates.

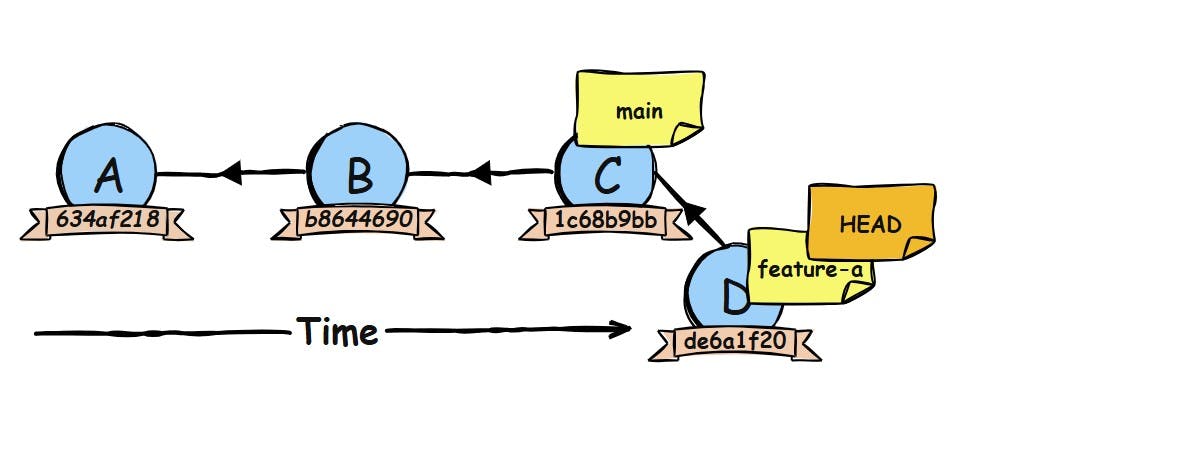

When you’re on the feature-a branch and you make a new commit, Git simply moves the feature-a sticky note forward to that new commit. HEAD stays attached to the branch label, so both HEAD and the branch label now point to the freshly created commit.

Nothing happens to the other branches. Main still points to the commit it pointed to before you’ve branched off, and now your feature branch is advancing on its own path.

Visually, it looks like this:

Git has:

- created a new commit (D)

- moved the feature-a sticky note (together with the HEAD sticky note) to point at commit D

That’s it. No copying of files. No rebuilding of history. Just one new commit and a tiny pointer update.

Meanwhile, the main branch is untouched, still pointing to its own commit. This is how branches naturally diverge: each branch moves forward only when you commit while HEAD is attached to it. Over time, this creates two lines of development (main and feature-a) each with their own sticky note marking their tips.

And if we create even more commits on our feature branch:

Quick detour! With the sticky-note model in mind, that familiar Git message,

“feature-a is 2 commits ahead of main”, suddenly makes perfect sense. It just means the feature-a sticky note sits on a commit that main isn’t pointing to yet. That’s it.

Another way to look at this is as a match score. After the branches split, both start at 0–0. Every unique commit on feature-a is a point for that branch, and every unique commit on main is a point for the other side. So when Git says “feature-a is 3 ahead and 1 behind main”, it’s just showing the score since they last played from the same starting point.

And once you understand that score, the next question becomes: how do you bring the two sides back together?

At some point your feature is finished and it’s time to bring your work back into the main branch. This is where merging comes in. Merging is simply the act of taking the work you’ve done on one branch and combining it with another. Because main and feature-a each have their own sticky note and their own chain of commits, Git now needs to figure out how to bring them back together. And depending on how the two branches have moved relative to each other, merging can play out in one of two ways:

- Fast-forward merge - where main is simply moved forward to the feature’s commit.

- Diverging history merge - where both branches have advanced independently, and Git must create a new merge commit to tie the two lines of development together.

Now that we covered all the basic components of Git, we will take a look at both merge scenarios in the next part of this blog and see what they actually mean in terms of your sticky notes and commit graph. We will Git there. See you next time!