“No pass, no entry” - a musician’s take on JWTs

Not too long ago, I started working on an assignment where I was responsible for setting up the security layer. I had done bits and pieces before - throw in some annotations, lock down a couple of endpoints - but this time it was different.

I had to build it from scratch!

JWTs, authentication flows, token validation, role-based access. The whole thing! I kind of knew what JWTs were - those long tokens you slap into a header - but I hadn’t really sat down and understood how it all worked. I knew just enough to be dangerous! Until now.

And as someone who plays drums in a band, I started to notice something familiar about it. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from years of playing in a band, it’s this: you don’t get into the venue without the right pass. Doesn’t matter if you’re the lead guitarist or the guy carrying the snare drum - no pass, no entry! The same principle can be applied when building web apps.

Your front-end is like the roadie showing up at the venue (a.k.a. your back-end). It wants access, it wants to get in and do its thing. But the back-end doesn’t allow everyone in. He has got to check some credentials.

And that is where JWT (pronounced as ‘jot’) comes into play.

The gig

Let’s say you’ve built a slick front-end app. It’s flashy, fast, and ready to rock. Now it needs to make some calls to your back-end - to fetch user data, update profiles, maybe even post some setlists. For the non-musicians among us, a setlist is a list of songs you, as a band, plan to play during a gig. Until someone in the audience yells a request and chaos wins.

Here’s the issue: how does the back-end know who’s knocking?

As a back-end, you don’t want to ask for a username and password on every request that comes in - that would be like showing your passport and filling out a form every time you walk past a security guard on tour. Exhausting. What we need is a backstage pass - a one-time signed token that says: “Yeah, this guy is with the band.”.

What exactly is a JWT?

JWT stands for JSON Web Token. It’s a compact, URL-safe string made up of three parts in the following format:

[header].[payload].[signature]

Let’s break it down:

- Header: says what kind of pass this is, and how it was signed.

- Payload: the actual info: who the token belongs to, what roles they have, and (very important!) when it expires.

- Signature: the real magic. It’s the tourmanager/organizer's signature - proof that this pass is legit and wasn’t faked in the parking lot.

Please don’t worry too much for now about the unknown words/abbreviations in the following payload example. A typical payload might look something like this:

{

"iss": "Creative Artist Agency",

"sub": "user123",

"name": "Dave Grohl",

"role": "drummer",

"exp": 1735689600

}

The payload is made up of so-called claims. Claims are key-value pairs. Nothing more, nothing less. They carry the info you want to communicate. By the way, the term claim isn’t JWT trying to be fancy. In real life, a claim is when someone says something is true. When you put these in a JWT you are embedding statements (claims) about an identity - and you are expecting the receiver to trust them … if the token is valid and properly signed, that is!

From a specification point of view (RFC 7519) none of the claims you put in the JWT are required. You could even send a JWT with an empty payload, but somehow that doesn’t sound very practical. Although they are not required, certain claims are recommended and often used in practice. For example, you will always find the exp (= expiration time) claim on a JWT when dealing with authentication and/or authorization.

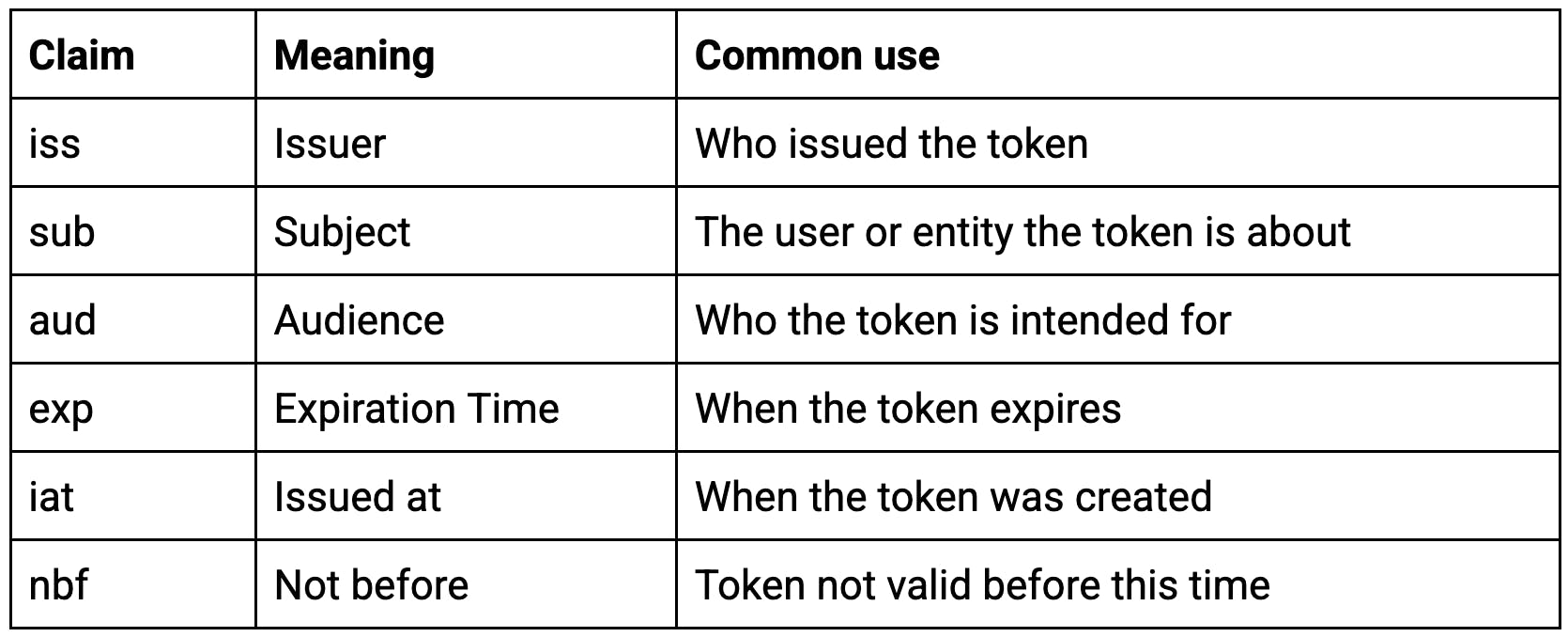

Commonly used claims:

Again, not required but extremely recommended. Especially exp, to prevent forever-valid tokens.

Show me the flow (of the tour)

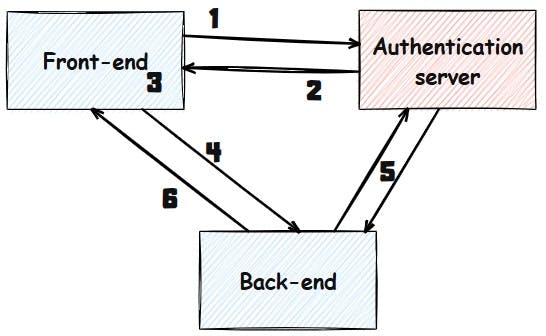

Let’s walk through the typical tour (aka JWT dance between front-end and back-end).

If we were to draw a picture of the whole thing, it would look something like this.

Overview

There are 3 actors involved in this process:

- your front-end

- your back-end

- an authentication server (e.g. Google or your own developed authentication server)

Step 1: Login

Your user logs in through the front-end. The credentials go to the authentication server. The authentication server checks them, and confirms they’re legit (or not).

Step 2: Signing the pass

If all checks out then the authentication server creates and signs a brand new JWT: a signed, encoded backstage pass containing the user's ID and role. It uses a key pair to do this: a private key, kept secret like the tour manager’s official stamp, and a public key, which anyone on the team can use to verify that stamp. The private key signs the pass so it can’t be forged, and the public key helps the backend know it’s the real deal - no need to call HQ. Once signed, the token gets sent to the front-end, ready to be flashed at the next venue.

Step 3: Store the token

The front-end stashes it - usually in memory or localStorage, ready to rock. This token will now go on tour with every API call to the back-end.

Step 4: Flash the pass

Whenever the front-end wants to access a protected route on the back-end (like /api/setlists), it adds the token in the Authorization header of the request and this looks like this:

Authorization: Bearer eyJraWQiOiIwODI2MDdmMi05NTBkLTRkNGEtOTk0Yy1kZWFkNDY3ZDQy... Step 5: Security check

The back-end receives the request, checks the token’s signature, confirms it hasn’t expired, and makes sure the user has the right role. But how do we check the signature? That’s where the public key part of step 2 comes into play. In order to check the JWT, the back-end needs the public key part of the key pair with which the JWT has been signed. What you usually see is that the authentication server exposes a special endpoint for retrieving the much needed public key. Only with that public key in hand can the back-end determine if the JWT has been issued by your authentication server, isn’t fake and/or hasn’t been tampered with. So, if everything checks out, you’re in.

Step 6: Backstage

If the security check succeeds then there is nothing left to do, other than executing the business logic and returning a response to the front-end. For as long as the JWT is valid, the front-end has access to the back-end.

Why use JWTs instead of just sessions?

Traditionally, web apps used sessions to keep track of who’s logged in. When a user logs in, the server creates a session - like writing their name on a clipboard - and stores it in memory or a database. Each time the user makes a request, the server checks that clipboard to see if they’re on the list.

Now, why then all this hassle of introducing extra components - an authentication server, tokens, signatures, the whole backstage circus with JWTs? Because you want your gig to scale! Sessions require the back-end to remember things - who’s logged in, where they’ve been, what they had for lunch. JWTs don’t. They’re stateless, meaning every server on your tour can check a pass and say, “Yep, looks good,” without phoning home to some central bouncer.

Think of it like this: instead of relying on one grumpy security guy with a clipboard at HQ, every venue on the tour has a scanner that instantly verifies your pass. They don’t need to call anyone, check a spreadsheet, or argue about your laminate - the token speaks for itself.

Beware of stage divers

JWTs are awesome, but not bulletproof. Here’s where they can trip you up:

- They expire - and until then, they can’t be revoked. If someone steals one, they’re in until it dies. With this in mind you should always keep the lifespan of a JWT as short as possible. As a general rule of thumb a JWT access token should be valid for just a few minutes (certainly not hours). By the way, saying that JWTs can’t be revoked isn’t 100% true, you can in fact revoke them, but only by adding a centralized check - like a token blacklist or by means of tracking token IDs in a database. But, by doing so this would remove their stateless (and therefore scaling) benefits.

- They’re readable - don’t put sensitive info in them. They're base64 encoded, not encrypted.

- Storage matters - don’t put them in a place where JavaScript can easily grab them if you have XSS vulnerabilities.

Refresh token has entered the building

As mentioned above, JWTs expire. Then what? Well, then we have to start the dance all over again. Or not? Think of your JWT as a temporary backstage pass - it gets you in, but only for a set amount of time. When it expires, you preferably don’t want to make the user log in again. You want the user experience to be as smooth as possible. That’s where the refresh tokens come in!

The refresh token is like a second pass that lives quietly behind the scenes - longer-lived, not used on every request. When the short-lived access token expires, the front-end uses the refresh token to ask for a new one. Kind of like walking up to the tour manager/organizer and saying, “Hey, can I get a new pass? Mine just ran out.” Important to remember: just like your JWT, do not lose this pass or show it off to other groupies!

This way:

- your JWTs stay short-lived which reduces risk.

- your users stay logged in without even noticing.

- your back-end still has control. In contrast to JWTs, refresh tokens can be revoked if needed.

VIP today, banned tomorrow

Think of the refresh token as a special, long-lived backstage pass - but one that the tour manager keeps track of on a list behind the scenes. If someone causes trouble, spills beer on the mixer, or just looks shady, the manager can strike that pass off the list. From that point on, even if they flash the same pass, they’re not getting a new one.

Some tours go even further with token rotation: every time you use the refresh token, the manager gives you a brand new one and burns the old one. It’s like swapping wristbands at every venue, so even if one gets stolen, it won’t work the next night. Unlike JWTs, which just roam free until they expire, refresh tokens give your back-end the power to kick someone off the tour at any moment.

Final encore

So, what’s a JWT?

It’s your digital backstage pass. Signed by the authentication server, handed to the front-end, and flashed at every endpoint of the back-end that asks: “Are you supposed to be here?”.

As a drummer, I’ve been let into a lot of venues with nothing more than a worn-out laminate pass on a keycord. If it’s signed, it's trusted. The same goes for your front-end app!